Old cameras fascinate me. I still have my father’s old Argus C3, my mother’s Kodak Brownie Starmeter, and a couple of vintage Instamatics, among others. Somehow I acquired an Argus 75 box camera and a busted Falcon Miniature — there’s a hole in the latter’s body where the shutter button used to be, so that the interior will never be lightproof again. I’m not sure whether those two were purchased by Dad or another family member, but I ended up with them.

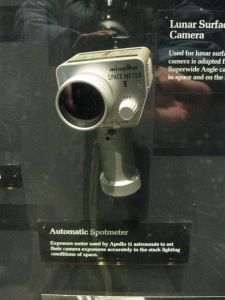

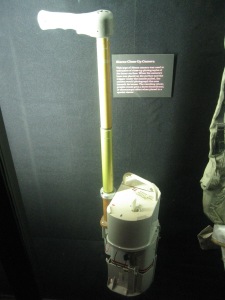

My interest in old cameras is certainly not limited to my personal stash. I totally geeked out when I was doing that OPN article on “Photography in the American Civil War” and got to spend an entire Saturday afternoon watching a guy making tintypes in Gettysburg, Pa. And I’ve written about the use of cameras and other optical equipment during the Apollo program in the late 1960s and early 1970s; it’s in the hands of the OPN editors now and will probably appear later this year.

So, imagine my delight at recent news reports that the widow of the first man to walk on the moon, Neil Armstrong, found a bag of his Apollo 11 memorabilia in the back of her closet — and, even better, lent them to the Smithsonian’s National Air & Space Museum. Best of all, the 16-mm Data Acquisition Camera that was supposed to have been left behind on the lunar surface came back to Earth!

I will have much more about this in my future OPN article, but basically, Apollo 11’s Eagle lander carried both video and film cameras. The video camera, mounted on the lander’s base, was pretty low-definition even by the standards of 1969 (that was the year the charge-coupled device was invented, but it certainly was nowhere near ready for prime-time broadcasting). The 16-mm motion picture camera was mounted so that it could look out the window of Eagle‘s ascent stage. It took much sharper pictures than the TV camera, but of course, no one could see those images until Columbia brought the film canisters (and astronauts) back home and technicians developed the film.

Many video clips of the Apollo 11 landing, such as this one, combine the film from the Data Acquisition Camera from the audio recorded by the Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston. What many people, especially those born after 1969, don’t realize is that the worldwide audience back on Earth could not see the film images in real time.

What the viewing public actually saw looked more like the CBS footage that you can find here and here: the live NASA audio combined with the voices of the television anchors, canned prepared animations, and the occasional “live shot” of people watching the coverage on giant screens. Because Armstrong had to steer around a boulder-strewn field at the last minute, there was a scary lag between the matter-of-fact animation’s depiction of the touchdown and the actual moment of contact with the lunar soil.

I can hardly wait until Armstrong’s stash goes on display at the Smithsonian. It will be awesome to see the actual camera that took some of the most exciting motion-picture footage of my lifetime, even if it wasn’t broadcast in real time.

(NASA’s own inventory of the objects appears here.)

Before I sign off, I’d like to mention a few other science-related stories that I’ve recently found interesting. I think I’ve mentioned most of them on Facebook, either on my personal or my professional page.

- First, a Pittsburgh startup company has gotten FDA approval for a new kind of internal tissue adhesive. I know someone whose husband could have really used this stuff after the abdominal surgeries he’s had over the past couple of years. The scientist who developed the adhesive is married to one of my high school classmates.

- A handheld Raman spectroscopy probe could help neurosurgeons find sneaky, aggressive cancer cells within brain tissue. This too is rather near and dear to me at the moment, because a close friend of a close friend is in hospice care for glioblastoma, which is pretty much the worst kind of brain cancer you can get. She just turned 46 years old, which is way too young to die.

- Finally, in March and September, you’ll have a couple of opportunities to help measure the brightness of the night sky where you live. You should have no trouble remembering the March date on which this citizen-science effort begins, because it falls on Super Π Day.